The concept of trapping people in a confusing space goes way, way back. But while escape rooms are all about a great night out, historical escape challenges—like mazes and labyrinths—haven’t always been about fun and games.

First designed for spiritual contemplation, it took quite a while for labyrinths to become the discombobulating entertainment we know today.

3000 BCE—Labyrinths of Bolshoi Zayatsky

|

| Image: Vitold Muratov (CC) |

Instead of being used to confuse and trap people, these structures were more likely used for religious contemplation or even potentially as traps to catch fish in low tides.

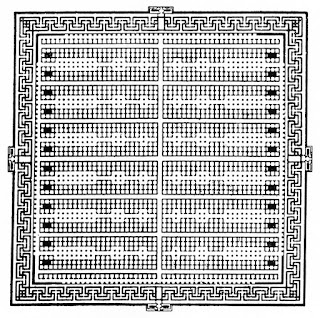

1800 BCE—The Egyptian Labyrinth

|

| Image: Archive of Affinities |

According to the historian Herodotus, the massive maze was made up of 3,000 rooms and housed the tombs of many kings.

1500 BCE(?)—The Cretan Labyrinth

|

| Image: AnonMoos (CC) |

Designed by Daedalus and his son Icarus (yes, that Icarus), the labyrinth was a site of sacrifice to the gods. Completing all these sacrifices was the Minotaur, a half-man/half-bull creature who was fed a stream of young kids every seven years.

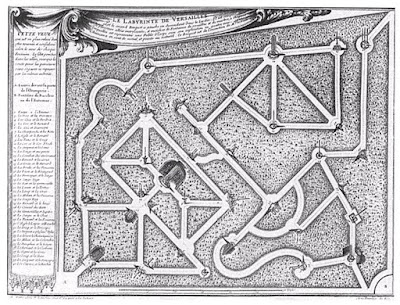

1675 CE—The Labyrinth of Versailles

Designed with an Aesop Fables theme, the 5.6-acre labyrinth at the Palace of Versailles was constructed out of 5-metre tall hedges and included 39 fountains. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in 1778 by Louis XVI.

1880s CE—Gustav Castan’s Mirror Maze

|

| Image: Dave Shafer (CC) |

Castan, who patented his invention in 1888, took a cue from the distorting House of Mirrors often found at fairgrounds, an attraction that in turn took inspiration from the famous Hall of Mirrors at—you guessed it—Versailles. Thanks, Louis!

You can visit Vancouver escape game Krakit seven days a week. We promise: no Minotaurs.